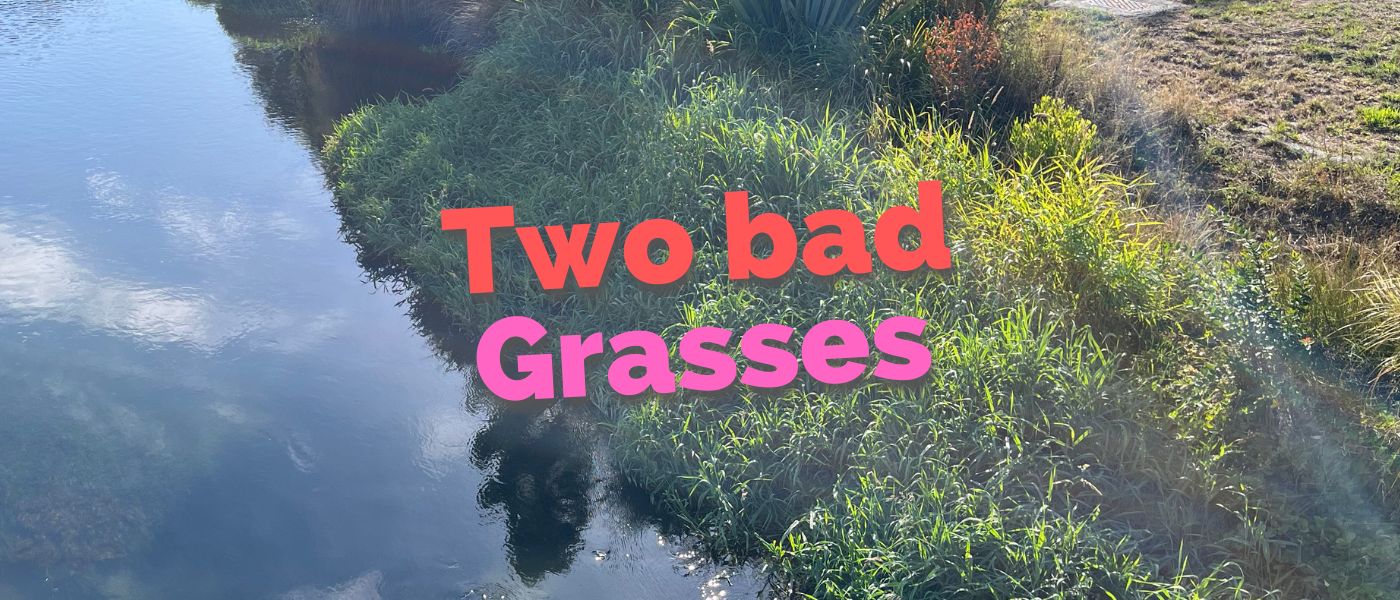

The riverbanks and margins of the lower stretches of the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River are currently covered in patches of lush, flourishing grasses that seem to be taking over much of the riverbank. Are these new? Are they useful? Are they wanted?

New Zealand is quite likely the most weedy country in the world; we didn’t get there by accident. The colonising farmers of the late 1800s and early 1900s went out of their way to bring in new species of plants to make up for what was seen as deficient native grasses; deficient from the point of view of nutrition for cows and sheep.

Canary Grass arrives So in 1874, Reed Canary Grass (phalaris arundinacea) was introduced to New Zealand as a pasture plant and also as an ornamental plant due to its upright, tall structure and leaf shape which made it a pretty showing when grown beside a pond or stream. It was relatively useless as a pasture plant because of its water preference. It did not take long to escape from farms and find a niche for itself. It now thrives under the shade of willows and open kahikatea forest, in wet grasslands, wet waste areas and roadsides and along the margins of water bodies like the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River. You can easily identify it: look for the tall grasses with a slight purple shading to the green of the pointed leaf.

Canary Grass spreads While canary grass is widespread throughout New Zealand, it has taken until quite recently for it to arrive in the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River. It probably arrived in the river in the early 2000s and quietly established itself in the lower reaches. Its spread has been inadvertently assisted by the Christchurch City Council’s regular weed-clearing operation along the river. As the weed-harvesting machine has chomped the clumps of canary grass that have intruded into the waterway or the workers with handheld weedeaters have merrily shredded the canary grass while clearing the riverbank, seeds and stem and rhizome fragments of the grass have floated up and down the river on the tides, gradually colonising the riverbank. Currently, you can find canary grass as far up the river as the Ensors Road bridge. Further down the river, the grass naturally peters out as the level of saltwater intrusion makes it too salty to grow on the river’s edge.

What canary grass does Once established, canary grass is capable of rapid colony spread. It typically spreads by shoots arising from shallow rhizomes which can extend over 3m per year underground and form a thick impenetrable mat. These rhizomes have numerous dormant buds that are the primary means for resurgence of the plant when above-ground growth is removed. Rapid expansion, early growth, and the mulching effect of a dense litter layer all work to facilitate the decline of competing native species. Only the native raupō appears to be able to out-compete canary grass in the river margins.

But then there’s Glyceria If you think Reed Canary Grass is bad, then let us introduce you to Reed Sweetgrass (glyceria maxima). Gylceria was brought into New Zealand in 1906 – as a stock feed. It is excellent feed apparently, but it only grows in wetlands where it grows abundantly, happily tolerating being eaten by stock while they wallow in the wetland. It is widely naturalised and abundant in most lowland parts of North Island, but it is more scattered and absent from much of South Island. It has been identified in the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River since about 2017.

A clump of Glyceria maxima

What does it look like? If you walk along the riverbank, look for a stand of bright green, vertical swords in a clump with perhaps some leaning over where the wind or water has bent them down. Glyceria contrasts its bright green growth with the blue-green of canary grass and raupō. Its growth tips are rounded like the shape of a boat. It does not like saltwater much so clumps of it are not currently found much downstream of The Tannery and so far, the most upstream clump is near the footbridge into Hansen Park by Armstrong Avenue. The riverbanks on Richardson Terrace and Clarendon Terrace are quite heavily infested with glyceria.

Glyceria is baaaad Glyceria maxima is named in a 2024 list of 386 environmental weeds in New Zealand prepared by the Department of Conservation. Glyceria forms a dense monoculture in nutrient-rich water, matures quickly, has a rapid growth rate, and overtops competitors including canary grass. Glyceria produces many long-lived seeds, and its rhizomes spread outwards, breaking off and rooting in any damp spot. It tolerates damage, grazing and pollutants, but the one bright spot is that it does not tolerate heavy frost and shade. Weed clearing efforts along the river really help to spread this weed.

It’s here now. Why don’t we just leave it ? We could. But, if you can, imagine a time in the not-too-distant future when, thanks to birds, people and machines spreading seed and plant fragments, this grass gets up to the retention ponds that have been recently opened in the Cashmere Valley, Wigram and at Te Kuru wetland; or into the Travis Swamp. It would likely out-compete and kill all the native grasses and plants in those basins. It would create an on-going and expensive need for constant removal so that the ponds were able to fulfil their flood-prevention role. Similarly, if this plant was allowed to spread up the river, the cost of continually harvesting it to allow the river to adequately drain the city would be substantially greater than it is already.

Death to Glyceria Given the importance to the river of removing this weed, the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River Network is embarking on a project to eradicate Glyceria maxima from the river, utilising Better Off Funding that we obtained from the Waihoro Spreydon-Cashmere-Heathcote Community Board. We initially thought we would be focussed on canary grass, but reed sweetgrass is much the worst of the two weeds. Currently, there are about 50 locations of Glyceria within a 5.25km stretch of the river, so it is still at a level where eradication is probably possible.

We are going to give it a good shot anyway.