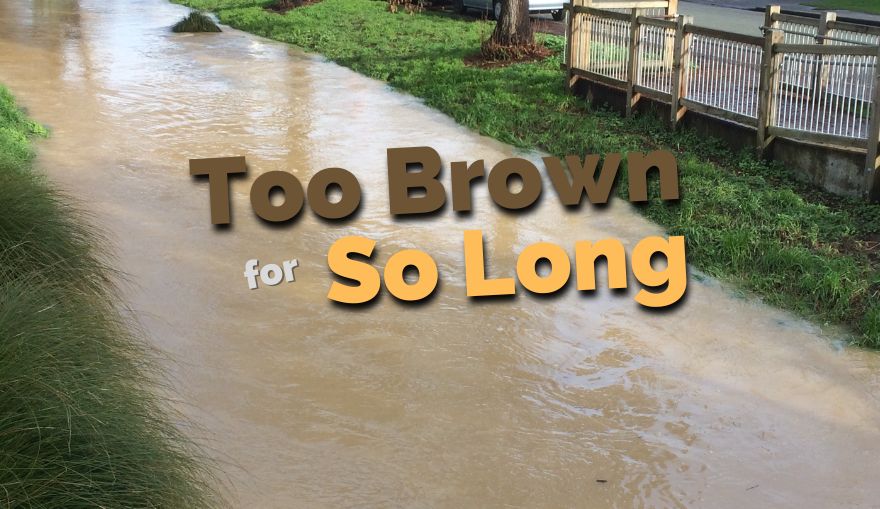

After rain events, it seems as if the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River has been flowing too brown for so long that there must be something wrong somewhere. What is happening to the river?

Why is the river running brown at all? That is the real question. It is running brown, in a way that the Ōtakaro Avon River does not during rain events. The cause is the Port Hills much of which is made of loess, a particularly fine-grained, wind-deposited soil. Loess is highly erodible, turns to a porridge-like mass when soaked in water and when mobilised by water moving across and through it, forms a suspension in the water. Unfortunately, even when left for weeks, loess does not totally precipitate out of suspension in the water.

So the brown look of the Ōpawaho Heathcote River is the result of erosion from the Port Hills and while all areas of the hills are erosion prone, some valleys contribute more sediment than others.

Where does the erosion occur? Starting at the very head of the river, the Hoon Hay Valley is one contributing source of erosion, mostly from farming and a little from housing developments although the latter have significant erosion control measures. The outflow from the Hoon Hay Valley is now diverted into the Te Kuru wetlands and retention ponds where it is joined by stormwater from large new housing developments around Halswell. While these housing developments can create some sediment flow in their construction phase, we expect that stormwater treatment systems in these new developments will minimise this as they mature.

The most prolific sediment contribution to the river comes from the Cashmere Valley. This can be verified by looking at the confluence of the Cashmere Valley Drain and the Cashmere Stream which occurs at Cracroft Reserve. See the video clip below as evidence. Be aware that the Cashmere Stream is a spring-fed waterway – it runs naturally clear until surface water enters it.

Why is the Cashmere Valley such a significant contributor to the problem of sediment in the river? There are five aspects to this:

- Roading: Dyers Pass Road, Summit Road and Worsleys Road all direct their stormwater into this valley. Roadside cuts erode easily into this stormwater, and the stormwater itself, given its speed and volume, is an difficult erosion vector as it moves down the slopes to the valley floor.

- Housing developments: In particular the Cashmere Estates housing development, still in its construction phase, produce a high level of sediment. The construction team use flocculants in retention ponds to try to reduce the level of sediment, but given the area of loess exposed, this is of limited efficacy.

- Christchurch Adventure Park: While the Adventure Park’s tracks team does its best to minimise erosion, tracks across the hillside are excellent vectors for erosion. Research into the best way of controlling erosion from exposed surfaces in the park has been undertaken and the operators have armoured a stretch of the stream near the cafe to reduce erosion at this point, but the park remains a highly problematic component in the erosion battle.

- Forestry: The head of the valley is a private forestry block. Felling of areas within this forestry block sets up erosion pathways.

- Fire: The Port Hills fires of 2017 exposed large areas of the valley slopes to erosion by removing vegetation. While some areas have been replanted, it will take a long time for revegetation to reduce the erosion risk.

But why is the river brown for so long? The short answer is that it is brown for longer because now it does not flood significantly in its lower reaches. The operation of the extensive Te Kuru retention ponds and wetlands, in conjunction with those in Cashmere Valley and at Wigram, means that millions of cubic metres of stormwater along with its sediment loading are stored during a rain event. As soon as the rain stops, these ponds are allowed to drain their stored contents into the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River – and that means that the river flows at a high level for quite some time. When the Cashmere Dam, currently under construction in the valley, is complete, that will be the final storage area in the system to become operational…and then the river will flow brown for even longer.

What can be done to reduce the erosion? Revegetation, particularly of valleys, is the only way erosion will be reduced. Currently, there are pockets of revegetation taking place, undertaken by the CCC Port Hills rangers, groups such as the Summit Road Society and private landowners. Good on them! However, there needs to be vastly increased scale to this revegetation, greater co-ordination and, of course, greater financing.

Port Hills Plan What the problem needs is a plan of the overall long-term solution – a Port Hills Plan that is focussed particularly on the issues of the north-facing slopes, that brings together the experience of those already working on the issues and which can be used to co-ordinate actions that address the sediment problem in a manner that the scale of the issue demands. It will not be easy! There are many issues to work around including fire risk and selection of plants but we have to start. The Ōpāwaho Heathcote River Network is pressing the City Council to accelerate work on a Port Hills Plan.