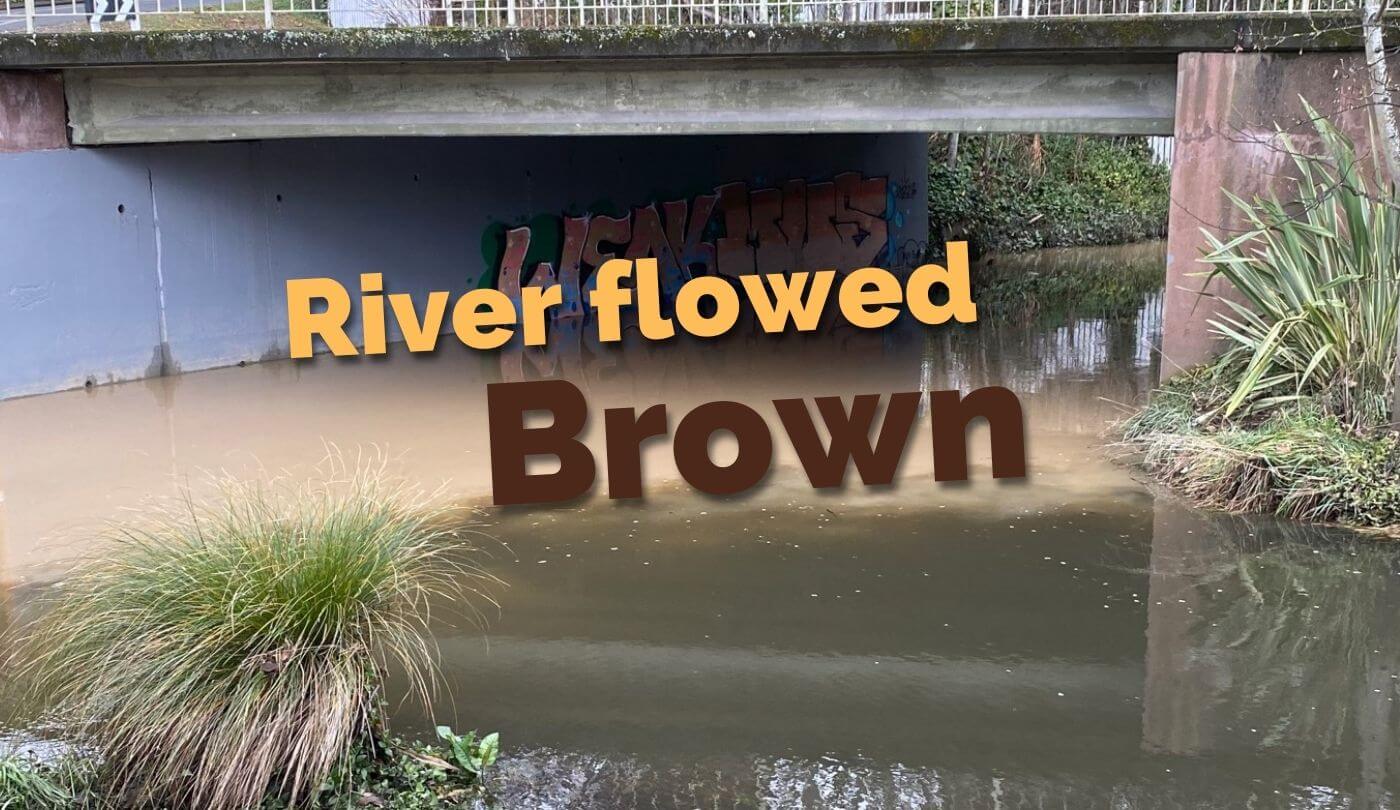

Following the highest recorded July rainfall, low-lying areas of Christchurch were largely spared the flooding that would normally be expected from such an inundation. But the river flowed brown for a week after the rain eased. Why?

Following the 2010 earthquakes, the Land Drainage Recovery Programme (LDRP) was set up by Christchurch City Council (CCC) to understand the consequences of the earthquakes on the city’s land drainage network. It lead to a number of projects to reduce the risk of flooding to a level that was close to what it had been prior to the earthquakes. Within the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River catchment, such projects included:

- Dredging the lower reaches of the river

- Stabilising the riverbanks through Cashmere and Beckenham

- Purchasing more than twenty residential properties which were likely to be flooded no matter what preventive measures were taken

- Investigating the possibility of raising riverbanks

- Building retention ponds and wetlands in the upper reaches of the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River

Taking action to minimise flooding was seen at this time as an imperative. The Council has certainly been active in following through on proposals and it deserves recognition for the positive outcomes from the expenditure of significant funds.

The building of the retention ponds and wetlands is not yet complete but they are at the point where they can be used to retain stormwater in quantity. During the latest large rain event, and for the very first time, the CCC was able to divert the flow of the Hoon Hay Valley Stream into the 100ha Eastman-Sutherlands Retention Ponds between Cashmere Road and Sparks Road. The Henderson Road basins were more than completely filled. Similarly, the flow off the Cashmere Valley was able to be retained in the ponds beside Worsleys Road and the Wigram Basins also performed well in retaining stormwater.

The result of this combined retention of stormwater prevented there being too great a rate of flow in the mid and lower reaches of the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River which in turn meant that the flooding that did occur was almost exclusively of roads and parks in particularly low-lying areas – areas which are expected to flood in heavy rainfall without endangering local dwellings. Inconvenience and restricted vehicle access in these areas is an acceptable outcome in times of high rainfall.

It should also be noted that the CCC has yet to build the last part of the Cashmere Valley retention system – a low dam across the valley that will retain a further 213,000 cubic metres of stormwater leaving the valley. It is due to start building the dam in 2023.

However, following the recent high rainfall, you will probably have noticed that the Ōpāwaho Heathcote River continued to flow swiftly at reasonably high levels and very brown for more than a week after the rain event. The lengthy high-level of flow was the result of the CCC deliberately opening selected gates to allow the excess water to empty out of the retention systems; it is an enormous quantity of water that is stored, and it must be released before the next rain event if the system is to keep the lower reaches from flooding.

Above: About 75m upstream of where the other video on this page was shot, the relatively lightly silted Cashmere Stream meets the silt-laden flow from the Cashmere Valley Drain which empties the retention ponds by Worsleys Road.

Above: Five days after the heaviest rain in July, 2022, the relatively clear Opawaho Heathcote River meets the heavily silted Cashmere Stream at Shalimar Drive.

The river flowed brown because the sediment that comes out of the Hoon Hay Valley and the Cashmere Valley will not come out of suspension to any significant degree even if stored in a pond for a number of days. The soil in the hills around these valleys is loess, a particularly fine wind-blown deposit. When it is mixed with water, the result is a terrible mess: a permanent suspension of sediment in the water. The only solution to this sediment load, which is killing the river, is revegetation of the Port Hills to reduce the movement of the soil.

Prior to human arrival, most of the Port Hills were covered in podocarp/hardwood forest. The plants which dominate the hills today are a result of both historic and current factors such as fire, grazing, rainfall, oversowing, logging and erosion. Returning the Port Hills to a forest dominated by matai, kahikatea, totara, mahoe, fivefinger and coprosma will be a long and difficult multi-generational exercise.

Regenerating the forest while avoiding unacceptable fire risk is just one of the issues. The Port Hills is a mixture of reserves and private land, so there will need to be wide consultation and agreement as the community endeavours to find solutions as quickly as possible to the wicked problem of sediment killing our river.